This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

I spent the first half of applicancy, my six-months’ time of formation in preparation for joining Madonna House, at Marian Centre Edmonton. That house was desperate for help at the time, so I got sent out to fill in.

So there I was, twenty years old and from the middle-class suburbs. This would be my first encounter with the men Madonna House calls “Brother Christophers”: the men on skid row, the men with chronic substance abuse problems, the down and outers, the homeless, those whom people in those days called “bums.”

I had heard all kinds of wonderful stories about how you encounter Christ in the poor, and I was very excited.

Well, “exciting” was not how I would describe the experience. The first thing and the main thing I experienced was the scandal of the poor. Seeing guys in so much pain was more than I could handle, and I was horrified by the whole experience.

Oh, individual people I met, I liked and some I had a good relationship with. But we were serving 1,100 meals a day at that point, so it was almost like a factory.

To see that amount of distress, that amount of pain in people and not be able to assuage it, touch it, fix it—all those things that as North Americans we want to do—was pretty horrifying.

I was only there for three months and on one level that was unfortunate, because three months is not long enough to break through that scandal.

So needless to say, though I overall enjoyed the experience of being in a mission house in Edmonton, I was glad to return to Combermere.

I finished my applicancy, made First Promises, and for a number of years, served in various capacities. Then one day, I was asked if I would go to Marian Centre Regina, another house where we serve the Brother Christophers.

I still had reservations about the Brother Christophers and being present to them. Oh, I had heard lots of stories from Michael Fagan and Jim Guinan (elders in the community) and many other people, about what a gift those men were in their lives and how much they had learned from them and so on.

But I had always figured that they experienced that because they were holy. That’s not for me, I thought. That’s not the kind of work I would like to do.

So when I was asked if I would like to go to Marian Centre and be on the staff there, I was very surprised because, despite my reservations, instantly inside of me, I knew this is what God wanted me to do. It was very clear, and it didn’t feel like a tremendous burden. So, actually, I was happy to say yes, and I was happy to go.

Even so, I was still really afraid, particularly of myself. I wasn’t worried about the guys or the work, but I was afraid of my own fear and my own reaction.

What would happen if a fight broke out or if somebody tried to break in the house at night and I was the only man around? What would my reaction be? I prayed a lot about that, and I said, “Lord, you show me. Give me the grace I need for whatever happens.”

I was only there about a month when a fight did break out in the dining room. Now in Regina, that’s extremely rare, in fact, very, very rare. Most of the people who come have a lot of respect for the staff and for the peace of the place, so they’ll avoid that kind of confrontation.

But anyway, here we were. I was in the dining room; I was in charge of the dining room. I was brand new, and I really didn’t know what I was doing or what was going on. What do I do?

I didn’t have time to think about it. I just stepped in. I separated them, and put one guy out one door and the other guy out the other door. I wasn’t angry, I wasn’t upset, and it went very peacefully. It wasn’t until afterwards that I realized God had answered my prayer.

This taught me something about trust: that God’s not going to put me in a place where he’s not going to give me exactly what I need to handle whatever situation comes up.

We hear that a lot—my grace is sufficient for you—but most of us don’t really believe it. We’re sure that we’ve just been pushed past the limit, and that God’s grace probably is not going to be sufficient for us.

Anyway, the next stage in this journey with the Brothers Christopher is to go from the scandal to what I would call companionship, sympathy, compassion, and a sort of identification with them, but not a complete identification.

This was the stage of taking on their suffering and their pain as my own in my head. It was kind of a heart/mind exercise, but not complete, and so the fruit of that became anger.

Anger that these people are marginalized, anger that they’re being treated the way they are, anger that their situation can’t be improved, that I can’t fix it, that Marian Centre can’t fix it, that the Church can’t fix it, that the government can’t fix it, that “society” can’t fix it.

So you go through that process of anger, and after a while that starts to go away, and you enter into another stage.

You begin to experience your own poverty in that anger and in your own poverty you come to realize that the Lord’s not asking you to fix it. The Lord didn’t create Marian Centre or Madonna House to fix people’s problems, particularly those of the people on the street. All he’s asking you to do is to be present there.

And finally you begin to enter into the last stage of identification with the poor—the one that comes through your own poverty.

One of the first things I was told by the director of the house when I arrived at Marian Centre was that there is virtually no difference between the poverty of the staff of Madonna House and the poverty of the people we serve.

I didn’t believe that at the time. I was not an alcoholic; I wasn’t on skid row. I didn’t experience that kind of pain and that kind of poverty. Sure, I had my problems but they weren’t that bad.

An image comes to mind: an image of the front door and the back door of Marian Centre. People come in through the front door for lunch in our soup kitchen or for clothing or a sandwich or whatever they need. They’re broken, battered, bruised, abused, marginalized, whatever word you want to use.

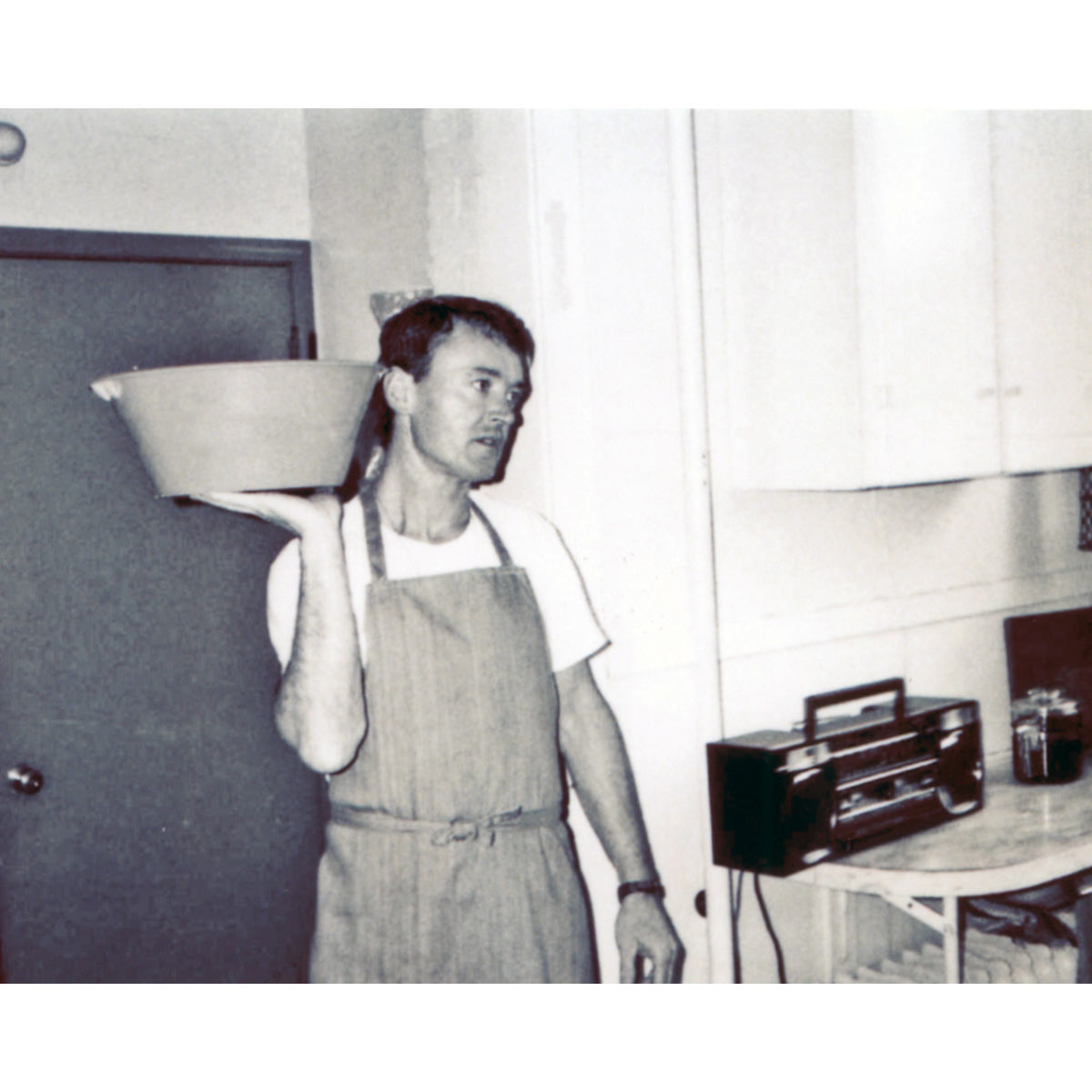

Other people come in through the back door to bring donations of clothing or food or to volunteer, serving the Brother Christophers by preparing food, cleaning, doing whatever needs to be done.

Sometimes I come in through the front door and sometimes I come in through the back door. Sometimes I am the poor man, and sometimes I am the one who serves.

I experience this within the Madonna House community as well. Sometimes I am Christ who is poor and wounded, Christ who is in need of anointing, in need of blessing, in need of friendship, in need of affirmation, in need of all kinds of things. And my brothers and sisters, or maybe just one of them, ministers to me.

At other times, I am Christ who stands before my brother or sister in need and provides them, or tries to—with blessing, with anointing, with healing, with friendship.

And so, through everyday life, there’s this constant experience of my poverty, my sinfulness, my neediness, which at times is overwhelming, and also the experience of the poverty of my brothers and sisters that calls me out of myself.

That’s our vocation.

There is a sign in Catherine’s cabin, one that the Madonna House staff are very familiar with: Pain is the kiss of Christ.

When I first saw that or heard that when I was 18 years old, I thought, “That’s really holy, but I don’t understand it. I don’t even know if I agree with it, but it’s probably true and maybe someday I’ll understand it. Pain is the kiss of Christ.”

Everything in our culture, in our society says no, that’s not right. Pain is bad. Avoid it. Get away from it.

But you come to a certain point when you say, well no, that can’t be true. There must be some value to pain; I’ll offer it up. But is it really the kiss of Christ?

Well, in some kind of deep and mysterious way, when we are identifying with one another, when we are present to one another either in our own pain or in the pain of another, whether it is that of our brother or sister in community or that of the “poor person,” we’re in that precise place where Jesus Christ who was crucified for us, stands suffering with us and for us.

We enter into that mystery of suffering, and only when we experience that and stand in it do we really start to know that, yes, pain is the kiss of Christ.

Every kind of pain is the kiss of Christ, if we can accept it as Christ offers it. I don’t think we can learn that any place else than that place where we experience pain—our own and that of our brothers and sisters.

It took, I’m guessing now, probably about six years, six years of becoming aware of my weakness, woundedness, and sinfulness, to come to the point of realizing that, yes, I am that poor—maybe even poorer than the man on the street.

When that happened, when that finally happened, then I could begin to reach that point that Catherine calls identification, that deep knowledge that my suffering and the suffering of the poor man and the suffering of Christ are one.

I am a poor man and Christ and the poor person in front of me and I are one.

From Restoration, January 2016