This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

Trouble in Canada, trouble in America, trouble (big trouble) in Ukraine. And trouble in a host of other countries around the world which perhaps don’t make the headlines in my daily newsfeed, but nonetheless count as much in God’s eyes.

Oh, we got trouble, as the song from the old musical, The Music Man, goes—“trouble with a capital T”.

I am writing this article on the day in late February when the bombs started falling in Ukraine. By the time this paper goes to print and you receive it and are reading this article, God alone knows what will have happened.

Yet here it is. April is upon us, and spring, and Easter. The hope of Resurrection dawns around us with the coming of new life from the cold earth and Christ from the tomb, even as the world’s winter and its deathly grip holds us fast in its talons.

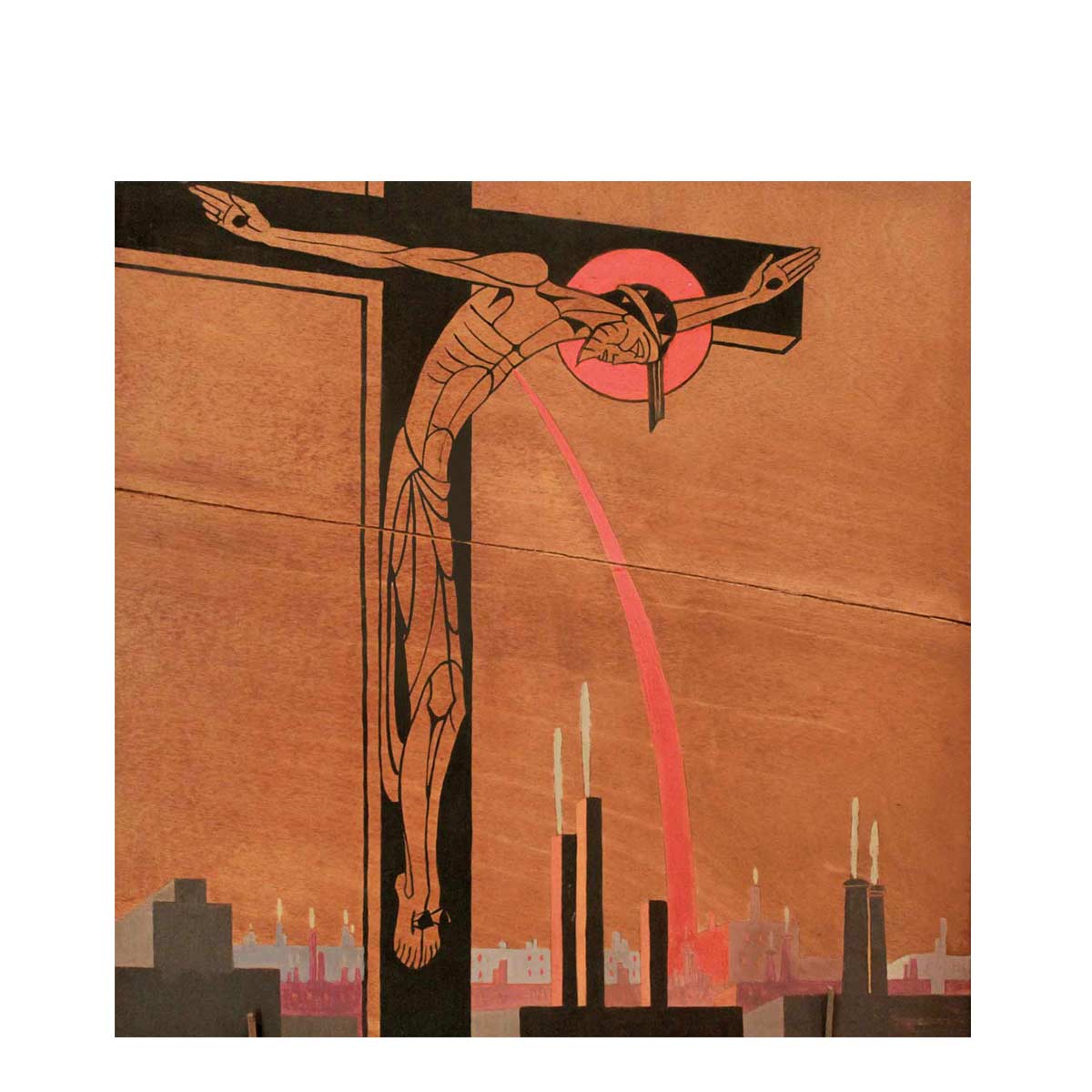

Perhaps it is a sign of the times that my attention this April is drawn back from Easter itself to Good Friday and the mysteries held therein. We are Christians; we are an “Easter people.” We believe in the Resurrection, believe that love and life and God will have the last word in every human story and in the story of humanity in its entirety.

We strive to be, then, in the evocative words of St. Augustine, an “alleluia from head to foot.” Joy is the clarion call, the rigorous challenge, and simply the duty of the moment of the believing Christian at all times and in all circumstances. By such a choice of joy we bear witness to our faith in the Resurrection of Christ from the dead and the promise of glory it holds.

But this does not remove the reality of the Cross from our lives and from the life of the world.

Until Christ comes in glory and every tear is wiped away, the Cross comes in and out of each of our personal lives and the lives of nations and peoples. Sometimes more, sometimes less, never wholly absent—suffering is and will be the common lot of humanity until the happy day when that will no longer be the case, that glorious future of which Easter is the sure hope and promise.

While it is a fool’s game to compare sufferings from one person’s life to another’s, let alone from one historical era to another, the world does seem, as I write this article, to be immersed more and more in an era of suffering and sorrow.

So it is good to linger on the reality of Good Friday, the day when God himself plunged into those immersive depths of suffering for all time and all people and took to himself the whole of it, forever.

The Church in its Good Friday liturgy contemplates this mystery in simple sparing terms. The Liturgy of the Word proclaims the story of Christ’s passion and death in the majestic austere tones of John’s Gospel.

The Liturgy of the Veneration of the Cross bids us to “come and worship,” to simply bow low before the reality of the gift of God that surpasses all gifts and our own capacity to understand it.

God the deathless one, died. Come, let us worship. The sinless one embraced all human sin and sin’s fruit, death. Come, let us worship. Life itself hangs dead from a tree. Come, let us worship.

And so we do, in our poor feeble way. A little bow, a genuflection, a full prostration, a kiss. It’s a small gift to return for so large a one, but that’s OK. We’re small people.

The liturgy ends with the reception of Holy Communion, as the fruit of Christ’s passion—his abiding gift of self to the world in the Eucharist—is once more made ours for the taking.

But it is the rite that comes between these two that more and more grips my attention as years go by and the world’s passion digs a bit more deeply into my heart.

This is the Solemn Intercessions where the Church pours out before the Lord all the needs of humanity. The Church, the world, the suffering, the poor, those who are of our faith, those who are not, those who are of no particular faith—all are brought in turn before the Cross of Christ for his mercy and care to descend on each according to the need of each.

There is a tremendous simplicity to this rite, even with the varying postures of kneeling and standing we assume in it. It’s as if on this day and at this time we have Jesus right where we want him—transfixed in our presence—and so we will bring him at length and in full, our list of needs, like children writing their Christmas lists to Santa.

We write our Good Friday list for Jesus, a somewhat different prospect, mind you. Well, for the Pope… and for our bishop… and all bishops… and the Church… and all Christians… and Jews… and believers in God… and disbelievers… and all who suffer and are afflicted….

You got all that, Jesus? We’re asking for mercy, mercy, mercy, mercy for each one and for all according to the need of each one.

There is a pattern for all our lives laid out here in this liturgy. We behold the gift of God, proclaimed in his word. We pour out our needs before him, confident that this God who has gifts for us, has loved us so well and so will hear our prayers.

We pour out our love for him, small and feeble as our little gestures may seem in response to so great a gift. And we receive the gift again, this time not in word but in deed, as the Body of Christ is given to us as food and drink, as life itself. And isn’t this the whole pattern and substance of life as a Christian?

And so as we enter into the glory of Easter and the beauty of spring (the two are irretrievably fused in my mind and heart), we do indeed carry the passion of the world to the foot of the Cross of Christ. Easter is our hope in this, the reason we persevere through seasons of affliction and darkness, sorrow and grief.

Christ is risen. Life is triumphant. Love is victorious. God is … well, God in the midst of it all, and his mercy and grace win the battle, win the war, and win our own hearts and souls to his kingdom where our joy will be undimmed and all will be made well, at the end of all things.