This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

One opportunity during this COVID-time when our usual ways of pleasures are limited—or at any other time, for that matter—is to discover or re-discover the joys of really looking at small, simple everyday things, in nature and elsewhere.

✧

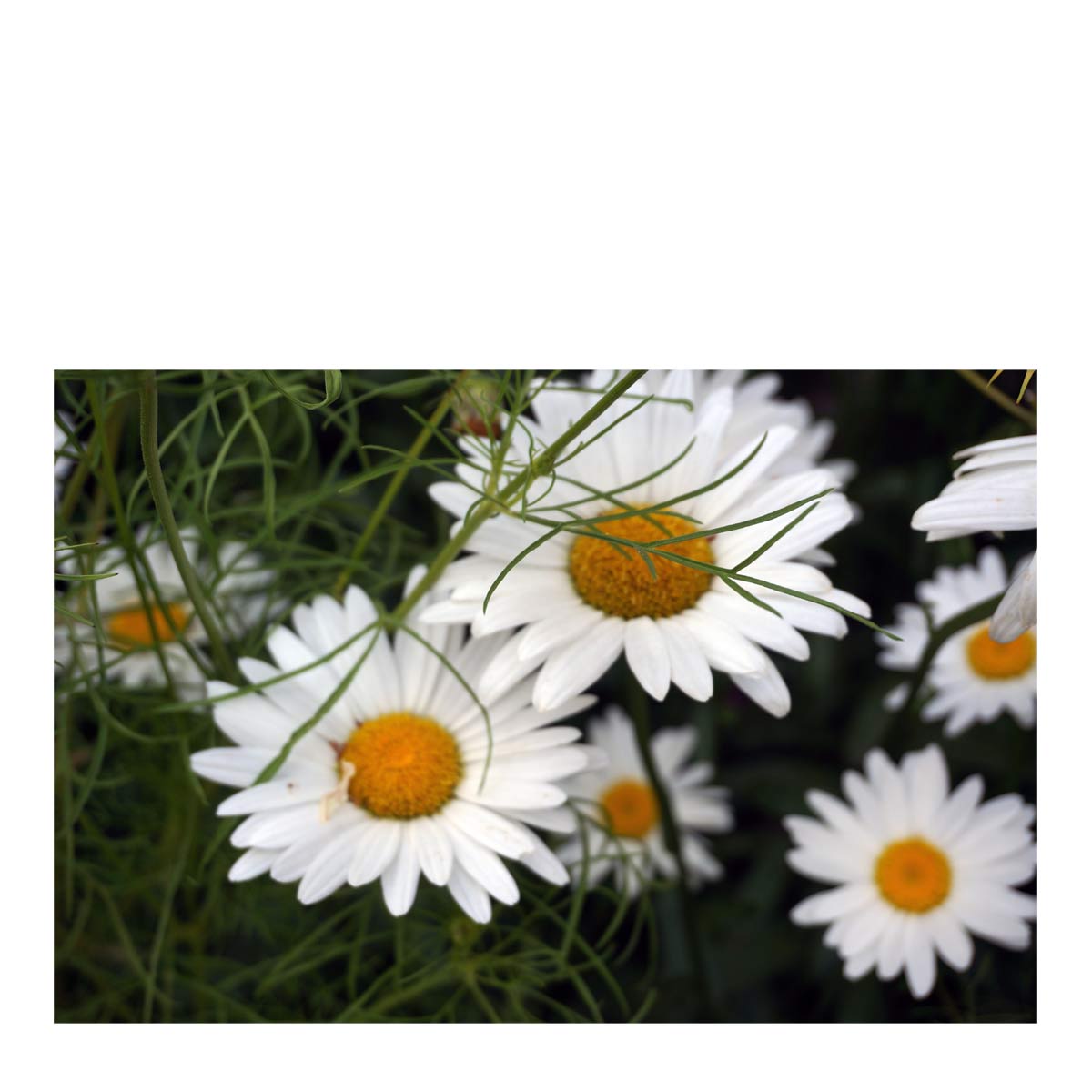

Dear God, our Guidebook and our Destination—where all roads end, where all roads come together: When I was a child my father used to sing me to sleep, sometimes, with a song about daisies, “Daisies Won’t Tell.” Today I learned that daisies will tell everything, if a person listens.

They were strung along both sides of the road I walk so often in quest of stones, which I collect. The daisies reminded me of the lamp posts that used to border the streets in Chicago a very long time ago.

I remembered how the lamp lighter used to appear each evening, just about dusk, carrying a lot of equipment, including a ladder.

He would place the ladder carefully against the post, climb slowly, and squirt a beautiful blue flame into the lamp. In a moment or two the lamp would burst into light—a miracle for the small boy watching.

“But God doesn’t go to all that trouble,” the daisies told me. “When he wants to light your path, he simply says, ‘let there be daisies,’ and the daisies are at your ankles.”

I realized then, Lord, that you have been hemming all my roads with daisies, ever since I was born.

There were daisies all about me, even when I wandered far away from you, far away from any thought of you. And I recalled some lines written by Janice Davis, in her whimsical poem,

“The Good Child’s Flowerbed of Beasts.” She classified roses as jealous beasts, pansies as humble beasts.

But, evidently, she didn’t find anything beastly about the daisy.

✧

“I think I like the daisy best.

It laughs and nods

and dances;

It seeks the meadow

and the ditch,

as vagabond as Francis.

and like that joyful

little man,

the merry clan of daisies

lift ragged arms

and shining eyes

to sing

their Maker’s praises.”

✧

“We’re not lighting only your path,” the daisies told me, “but all God’s bounteous table. Let your flat pigeon-toed feet go slowly up and down the road, and let your eyes be less gluttonous than they appear. See slowly, even as you eat slowly.

“You can’t see everything at once. Do you want to get indigestion of the eyes? Eat with your ears also, and with your sense of smell.”

In the light of the daisies, I saw that the raspberries were ripe. Lord, you waited for me in ambush, in a sweet raspberry jam bush. I helped myself. What a feast!

A red bird flew across the road and vanished into a green world of maple leaves. It was a crimson flame, Lord, more exciting, and more miraculous than the blue flame of the old lamplighter.

Quite a distance ahead of me I saw something that looked like a mahogany four-poster bed, rocking in the road. When I came closer I saw it was a horse. A rocking horse, but not a rocking horse.

He was rolling in the dust, his legs up, kicking with joy. A black squirrel watched him for a time, then went to investigate the rumor that hazel nuts were coming back. A big gray rabbit sat in the dust and looked at me a long while. When he was sure I wasn’t a carrot, he disappeared into a bush.

A green and yellow leaf came skittering across the dirt. It was too pretty to let lie there. I picked it up and thrust it into the basket of stones I carried, stones carefully selected from your infinite display.

Butterflies kept flying around me, as though I were a freak that they might study, or as though they were gaudy angels wondering what on earth you saw in men that you should love them so. And the sky looked down at me with the serene blue wonder of a child.

The dust was thick. And I remembered our Father Briere. On the eve of his silver jubilee, he said a prayer to you. “Lord, tomorrow I celebrate the twenty fifth anniversary of my ordination to the priesthood. And if you want to give me a gift, give me a little rain.”

He didn’t want rain for himself, of course. What can a priest do with rain? He wanted it for the farmers, many of whom had suffered greatly in the long drought. When he woke in the morning, it was raining. And he gave you thanks.

I continued to eat the daisies with my eyes. In fact, I gorged on them, Lord.

But I had time for your other dishes of sights and sounds and smells. Through fields wide and narrow, I went hunting yarrow, thinking of candles that would send up to you, when they burned, yarrow aromas as pungent and pleasant as prayer.

I lingered, for a few moments, near our herb garden, and sniffed a piece of heliotrope given me by the girl who was working there, a girl who looked as much like a daisy as the daisy looked like her.

Finally, I came home, to stand idly by and watch the young people working in the yard. They work efficiently, happily, earnestly, singing as they worked. They make me wish I were a daisy too.

But there is too much dust on me. I shall never be anything but a thick-skinned thistle rooted in the hard clay of a ditch that runs smack through the daisy field, and I need the sun of your love and the abundant rain of your mercy.

With much love,

Your thirsty thistle, Eddie.

—Excerpted and adapted from the column “A Love Letter to Almighty God,” Restoration, August 1965