This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

It was the first day of my new assignment, of my first posting to a foreign house—Carriacou, a tiny island in the West Indies. I was told that I was going to be the laundress for our house. We were, at the time, ten members of Madonna House—three of whom were Carriacouan.

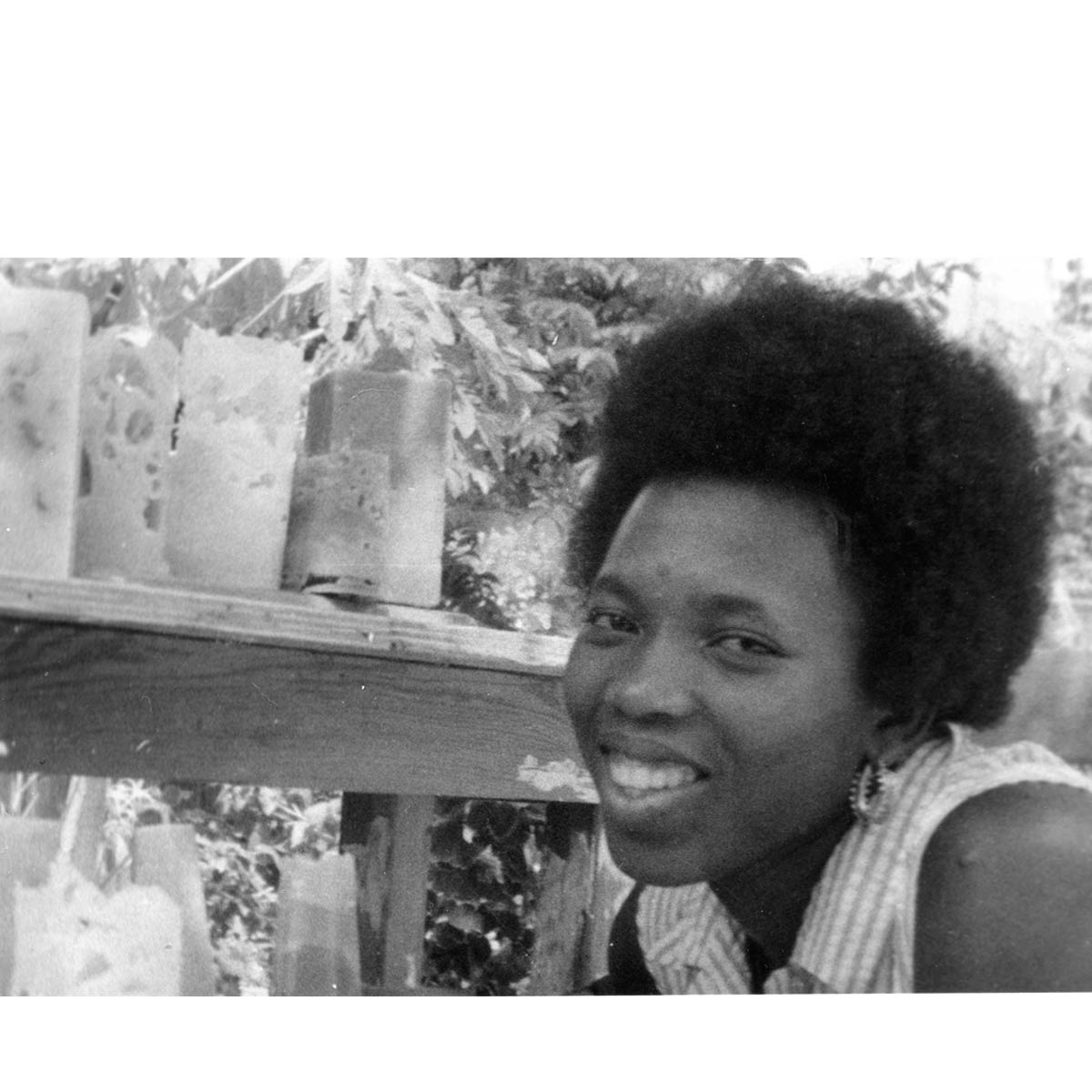

Irene DeRoche, one of the Carriacouans , was going to teach me the job, a job she had been doing for quite a while. My taking it on would enable her to get out and work more directly with the people.

The first thing to know about this situation is that laundry on that little island—at least at that time—was not like laundry in the United States or Canada where you had automatic washing machines, driers, laundromats, and abundant hot water.

In Carriacou, in 1976, laundry for ten people was almost a fulltime job, and it was highly skilled.

Why? Well, first of all, conditions were different—and challenging. The water was tepid, not hot, and, on that dry island, scarce. Water was precious, and in order to have what you needed, you had to use it sparingly.

Moreover, on a tropical island, clothes get sweaty and dirty faster, and salt air and a powerful sun wear them out and fade them faster than happens in a temperate climate.

People were poor and clothes were precious; they worked to make them last as long as possible. Moreover, they took pride in their clothes. They wanted them really clean—especially the whites really white—and completely wrinkle-free.

So Irene and I began. We had an old-fashioned washing machine—one that only agitated and had a wringer which you turned with a handle. Because water was scarce, you washed all the clothing in the same water. Then you changed the water and did all the linens in a second load of water.

Irene taught me how to sort the clothing for the different loads. Into the first load would go the cleanest, dressiest, lightest-colored clothing, and gardening clothes would obviously go in the last load. And there obviousness stopped.

One big factor—besides lightness of color and degree of dirtiness—in deciding where to put a dress was where and when it was worn: Sunday, street, house, or garden—every dress fell into one of these categories. For example, something that was considered too worn to wear on the street could be worn in the house.

The distinction was not according to style and dressiness, but according to the degree of worn-outness. As time went on and the dress began to wear out, it would go into a lower category, when the water was less clean.

So, sorting the clothing, like everything else in Carriacou laundry, was not a simple matter. Irene knew the current “category” of every dress. Would I ever learn that? And if I did, how would I ever remember it?

Then there were the whites. They had to stay really white. You made sure they were in the first batch and then you soaped them with a special blueing soap and laid them out flat in the sun on stands called “bleachers.”

It took a while before I could even see the different degrees of whiteness. I never did figure out how to know when they were considered white enough.

We examined every piece for stains, and then we would work on them. When I proudly discovered a small stain that Irene seemed have missed, she said, “I’ve worked on that one already; it doesn’t come out.” Irene seemed to know every detail about every piece of clothing.

Some things such as towels needed scrubbing on a scrubbing board—another skill because you had to scrub hard enough to get out the dirt but lightly enough to avoid wearing the item out.

And so we worked together. How long did we do so? I don’t remember, but it seems like it was weeks; it probably was. Was I getting it? Irene didn’t say much. I think she expected me to learn mainly by watching—a method that doesn’t work well for me.

She may have said something to the director, Trudi Cortens, because somewhere along the line, Trudi said to me, “I just want you to know that no North American has ever mastered the laundry to West Indian satisfaction.”

One day, Irene threw me a curve ball. She said, “You are going to have to learn how to read the sky.”

“Read the sky?” I repeated, stunned.

“Yes,” she said. “You need to know when rain gon’ come.”

She never did attempt to teach me this, but one day, when all the clotheslines were full, the sky was getting darker and darker.

“Rain gon’ come,” I said proudly.

Irene looked up. “We have 45 minutes,” she said, “and we need to get things as dry as possible before we pull them in.” Then she continued to work.

At some point, she said, “Now!” and out we went to quickly pull everything off the line.

I am not exaggerating. We had just gotten everything in, when suddenly the rain came—in torrents!

Had I been in Carriacou longer, the director seeing me work, would have known that I am the last person able to learn something that requires such close observation. I am really weak in that ability. Looking back, I can see that the end of this story was predictable.

The day finally came when I was told I would do the laundry alone. And so I did. For one week.

At the end of the week, the director came to me and told me that each of the three West Indians had come to her separately and told her their clothes weren’t clean enough—that I probably wasn’t sorting them right—and that if I continued to scrub the towels so hard, they would soon wear out. (How did they see all that?)

That was the end of my laundering days.

This story happened 36 years ago, and looking back on it now, I see much more in it than I did then. Back then, I tried to do little things well for the love of God—a part of the essence of the Madonna House vocation—I think mainly out of obedience. I found it hard and was not good at it. Plus it took a long time before I understood it.

But over the years, I have come to see that simple, ordinary, real things, have hidden depths and that if we respect them as creatures of God, pay close attention to them, and take good care of them, they will draw us into those depths and teach us much.

I am for sure not suggesting that we do laundry the way it was done in Carriacou. There are other ways that this connection can happen—through cooking and other housework, gardening, crafts, and some jobs, for example. Or to put it more simply, doing little things exceedingly well for the love of God will lead you into those depths.

After I left Carriacou, I never lived with Irene again. I only saw her briefly from time to time.

But after her death, from what people were saying about her, it was clear that she had gotten very good at picking up the subtle clues as to what people were feeling and needed and was thus able to respond to them with love accordingly. I suspect that the way she did the laundry was not unconnected to this.

Our foundress, Catherine Doherty, in teaching us to do little things well with love, told us that we would treat people the way we treat things.