This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

In a book on Islam by a Muslim convert to Christianity, the author gave his answer to the question: What can we do to help bring peace between Muslims and Christians?

He talked about the Muslim immigrants among us, and what he said brought to mind a story I read in Restoration many years ago, a story not about a Muslim, but about a little Black boy in the 1960s. Here it is.

editor

***

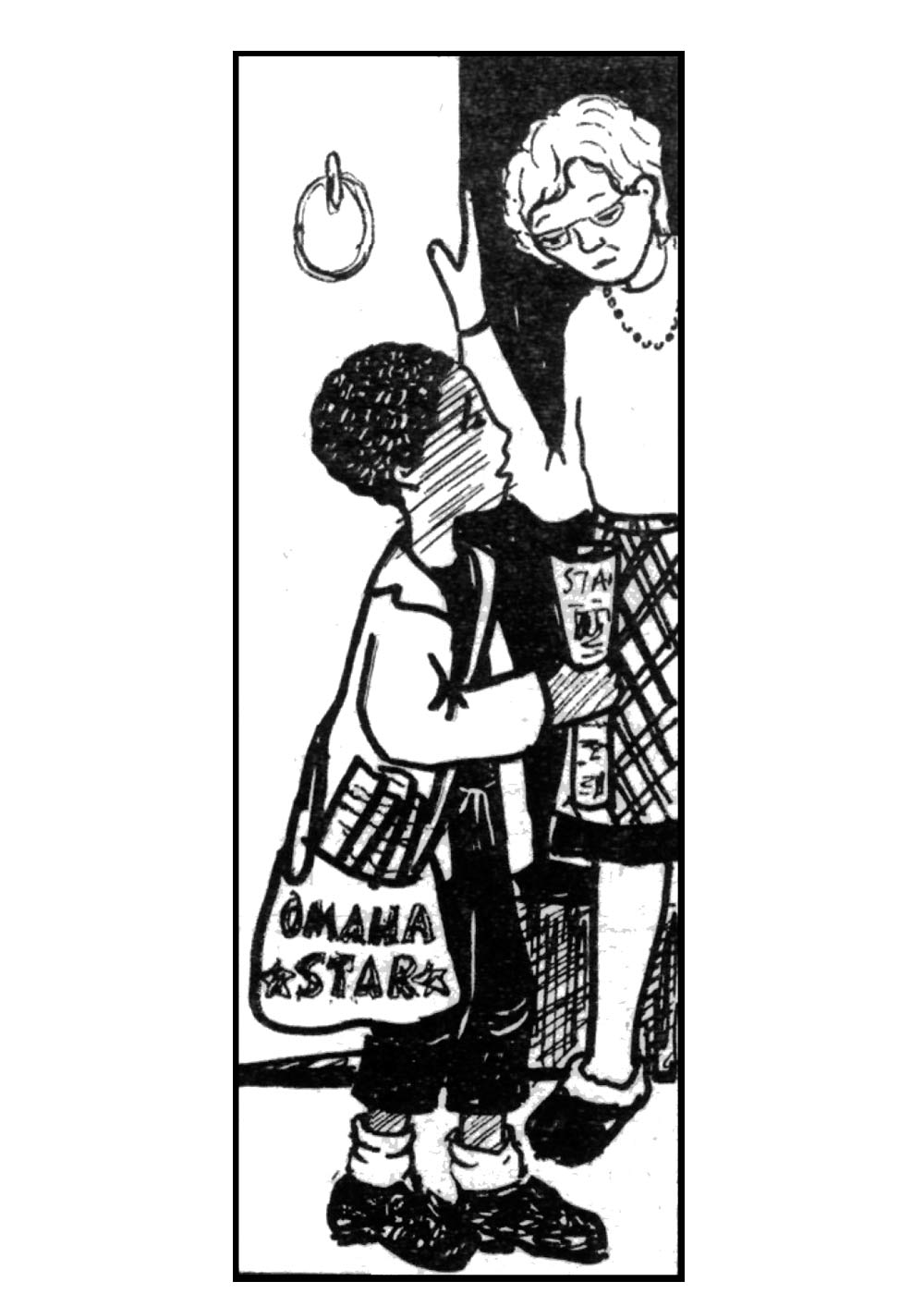

I was a little Black boy about eight years old. On a cold wintry day—one of the coldest and most wicked my flesh and bones had ever endured—I was out going door-to-door, block-to-block, mile-to-mile, selling for a dime apiece the Omaha Star, the only “Black” publication which existed in Omaha, Nebraska, at the time.

The shoes I had on were hand-me-downs, one size too big and bereft of shoe laces. I had gloves on, but for all the good they did me after being out in that severe weather for two or three hours, I may as well just have removed them and stuffed them in my pocket!

I didn’t have a scarf or a collar coat button, either of which could have offered my neck and face a measure of protection from the furious gusts of wind which must have been reaching up to 35 miles per hour, literally knocking me over a few times. It never occurred to me that I could actually die of exposure.

Nor did it seem to occur to the Black faces, which after hearing my tepid knocks on their doors and my chilled, pathetic, and stuttered, “Dada-da-do you wanna-wanna buh-buh-buh-buy an Omaha Stuh-Stuh-Star?” would politely, and sometimes not so politely answer, “No,” or “Not today,” or “I already have, thank you,” and proceed posthaste to shut their doors in my freezing face.

Mind you, it was not that these people were naturally ornery, or naturally intolerant of children not their own, or holding suspicions that this eight-year-old child might have wanted to mug them; for the fact is, at that time around 1962, Black folk in that city still harbored spontaneous, communal feelings for each other.

The Civil Rights Movement was still going strong down South, and its impact and unifying inspiration reached deeply into the recesses of Omaha’s Black community and served to strengthen its communal bonds.

It was here in this community where I could roam the length and breadth of it without ever having to fear, or fear inviting the fear of my immediate familial elders for my safety.

But on this God-forsaken day, I had at the wrong time, day, and space, overextended myself. I was at least three miles from home.

The weather was physically and even psychologically prohibitive of human warmth; and it was Saturday, one of only two full days out of the week left by the ruling class to workers for the latter’s own devices and/or vices.

If ever I believed in the concept of hell, then that predicament I found myself in 24 years ago, approximated it more than anything else I have suffered since. The circulation had gone out of my feet and hands. The twin trails of my running nose had by now turned to ice. I wanted to cry, but I was too cold to do so.

Perhaps for the sheer sake of survival, I should have entreated one of those Black faces to let me in for a while until I warmed up; but for the life of me, I could not make my tongue say what every other fibre of my being urged it to say.

I was literally dying on my frozen, frost-bitten feet, but my survival instinct seemed not to have been aware of it. Or if it was, you wouldn’t have known it by my behavior.

It seemed that I was content to let “fate” take its course, as my own mind and will to live took a back seat.

Finally, after the cold became too unbearable for me to tolerate any longer, I determined that the next person I called on would hear my plea for sanctuary.

Accordingly, cold and shivering, I headed my stiff legs and frozen feet up the snow-covered walk of a brown and white, two-storied house, trudged up the steps, and rang the doorbell. To my utter chagrin, the face which appeared on the other side of the screen door was not Black, but White!

“Ye-e-sss???” she drawled in a small, timid voice. She must’ve been about sixty, about five feet tall, with gray hair. “Can I help you?”

I wanted to cry. No way could I believe this woman or any other White person would actually want to help me or purchase a Black newspaper from me. Nonetheless, through chattering teeth, I managed to ask her if she wanted to buy an Omaha Star.

She considered me for a moment, told me to hold on, and disappeared from my sight. When she reappeared, she invited me inside and instructed me to sit on the living room couch, which I gladly did. She then proceeded to ask me what my name was, and I told her. Then she introduced herself to me.

Remembering the bourgeois manners inculcated in me from almost the first day of my birth, I replied, “How do you do, Mrs. Whiteson?” (I don’t recall her real name.) “Why fine, thank you. Would you like to take off your jacket?”

I answered, “Yes.” She took my coat into an adjoining room as a man whom I took to be her husband emerged from another room carrying a small tub of water.

He was at least a foot taller than she, bald at the top, with a wide, benevolent grin.

“How ya doin’, Sport?” he asked.

“Fine,” was my reply.

“I’m Mr. Whiteson. What’s your name?”

“Steve.”

“Well, Steve, let’s get those shoes and socks off and see if we can get some circulation back into those feet of yours.”

He removed my shoes and socks and had me stick my feet into the pan of soapy, lukewarm water; whereupon he began to wash and massage them. Afterwards, I was treated by my hosts to cookies and warm milk.

The next thing I remember is being gently shaken and asked if I was ready to leave. I said, “Yes,” though in actuality, I would have preferred a little bit more sleep.

My socks had been replaced by two brand new pair, both of which were slipped onto my feet by the mister of the house.

My shoes, now possessing shoe laces, were slipped on next. Then came my coat upon which the Missus had sewn a top button. She also thoughtfully provided me with one of her scarves.

We subsequently said our good-byes, but not before Mr. “Whiteson” had given me a brand new half-dollar piece with the admonishment that I not turn it in with whatever monies I had collected as a result of newspaper sales—that it was mine to keep for myself. Then we parted company.

That was the first and last time I ever saw that generous couple. And this is the first time I have the occasion to recall, discuss, and examine the significant role these two people played in my life, how much they contributed to my growth.

Would it be safe for me to assume that I could expect the same amount of warmth and compassion from any other White person under similar conditions? Or are White people like the “Whitesons” merely exceptions to the rule?

When Mrs. “Whiteson” appeared at her door in response to my ring of her doorbell, it was not herself as an individual personality I initially saw, but a representative of a race of people which specific experiences in my life had taught me to hate and avoid.

I couldn’t believe that she would or could offer me succour simply by virtue of her being White and I being Black. The most I expected from her was a polite, “I’m sorry, but not today.”

Happily, my preconceived, mental construction of her did not conform to the reality. She did not turn out to be the ogre I had expected, but instead proved to be as human as any other warm, gentle, and sensitive person I had met.

What this meant in practical terms is that I had now to modify my conception of White people as all being bad to one which would allow the recognition that there were actually differences in the same species.’

Why they were different from the ones who oftentimes destroyed my mother’s peace, and the ones who had led my neighbor to the conclusion that they were all “devils” I did not know. The neighbor never bothered to go into details, and my mother avoided the question altogether.

But when the racial war alluded to by my elder two years earlier did finally break out between White and Black, I decided that people like the “Whitesons,” should be spared.

Today, I would hope that there can be peace between the Black people and the White people, and not war!

But not just any ol’ kind of peace; not the kind of peace based upon the stultification of one race in deference to the other, but a peace based on justice, equality, and respect for one another.

Adapted from an article in Restoration, January 1987