This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

If you were to ask me, as people do occasionally, how I heard about Madonna House, I could answer simply that a friend told me about it. But how we became friends and how she told me about it, well, that is a story worth telling.

Audrey Monroe was a middle-aged African-American woman living in Harlem, the largest African-American ghetto in New York. For seven years in her younger days, she had been on the staff of Friendship House Harlem, one of the apostolates Catherine Doherty founded before Madonna House.

I was a young White woman also from New York, who had left the Church and was searching, searching for I-knew-not-what. My search had led me into the 1960s counter-culture. At the time we met, 1969, I was living at the Catholic Worker Farm, a counter-culture community about a hundred miles north of “the city.”

Audrey’s husband Joe had been with the Catholic Worker, and they had driven to the farm to spend the weekend. For some reason I have long forgotten, I needed to go to the city. I asked them for a ride, and they said yes.

Joe and Audrey were night people, and we didn’t leave until late. By the time we got to the city, it was at least midnight. To avoid taking the subway alone from Harlem, which would have been dangerous at that hour, and to avoid asking these people I had just met to drive me to my mother’s place, I asked if I could stay overnight with them. They said yes.

The next morning, Joe left for work and Audrey invited me to breakfast.

We ate together, and Audrey started talking. She talked and talked and talked. By lunchtime, we were still sitting at the table.

She offered me lunch, and we continued talking—all afternoon! I helped her make supper. Joe came home and we all had supper together, with Joe, of course, joining in the conversation. Then all evening, it continued.

Would you believe I stayed there five full days! The only thing I remember doing besides listening and undoubtedly talking, too, was going grocery shopping.

It must seem strange now hearing that I just presumed on Audrey’s hospitality, just stayed on. But in those days, in the counter-culture, people travelled a lot and stayed wherever they could.

But why did I stay so long? All I can say is that, as happened with the disciples on the way to Emmaus, my “heart burned within me.”

Audrey talked about Friendship House and Catherine Doherty and told me the story of her own life. And she talked about what it’s like to be Black in America. About all of this, she told numerous stories. I was spellbound.

Somewhere along the line, I remember asking her, “Why are you telling me all these things?”

She said, “Two reasons. Your father, (my father, who was deceased, had been a Friendship House volunteer) and I believe White people need to know what things are like for Black people. When someone is open, I tell them.”

What a crash course! What an education! It was only later that I realized it was even more than that.

As I said, Audrey told me lots of stories about Friendship House and Catherine Doherty. She talked about the staff and volunteers, about the community life, about the fun they had, and about helping the poor and working for inter-racial justice.

I said, “Oh, I wish Friendship House was still around. That is exactly what I am looking for. Except for the religious part.”

Audrey said, “Catherine is in Canada now, and she has a community there. But it’s different. It’s called ‘Madonna House’ and it’s like a secular institute.* You wouldn’t be interested in that.”

“No,” I said, “I wouldn’t.”

What happens after you’ve entered someone’s life and heart that long and that deeply? Well, for sure, we remained friends. Or should I say that she was my mentor? For it wasn’t only during those five days that I learned from her.

After that, I would visit from time to time. I have no memory of how often. But always, I felt so at home, so very loved and accepted.

My search was continuing. I hungered for meaning in my life. I wanted to help people. I wanted to change things. I was looking for a way of life different from what I saw around me. Fundamentally, I was looking for God, though I did not know it.

A year or so after those five days, I decided to visit my relatives in Quebec. Maybe their life on the farm would be better. Maybe I would stay in Canada.

Canada? That’s where that Catherine Doherty that Audrey had told me about was. And where she was, there was a community. While I was in Canada, I could visit there for a week or two.

The rest, of course, is history, but my vocation story is for some other time. Suffice it to say that it was at Madonna House that I returned to the Church and, just a few months later, that I found my vocation.

After I joined Madonna House, in the early years, I mostly went to New York for vacation. Moreover, at one point I stayed there for four months, taking care of my elderly aunt.

Whenever I was there, I would visit the Monroes. Often it was a refuge, for there were difficulties in my family. A couple of times, others were at their place as well.

When someone expressed surprise at a person the Monroes had befriended, Audrey replied, “Never be surprised at who you find at our place.” Joe and Audrey accepted people unconditionally—though they also complained about some of them!

A few they took on deeply. They “unofficially adopted” an immigrant from Africa, who continued to be family to them for the rest of their lives.

They never abandoned the struggle for social and interracial justice, something they’d both worked for in their youth. When their landlord neglected their building, they organized the tenants to buy it and run it as a co-op. When their local hospital was scheduled to close, they helped organize a group that fought to keep it open.

Two memories of my visits after I went to Madonna House stand out. One was Sunday Mass at the most alive parish I have ever seen anywhere.

During the announcements, the priest asked if there were any visitors.

Joe introduced me saying, “Do any of you remember Catherine Doherty? Well, she’s in a group in Canada now, and Paulette here is a member.” I wasn’t the only visitor introduced, but I was the only white person in the church.

At the coffee hour afterwards, person after person came to me mostly asking, “How is Catherine?” and also saying, “I was a cub,” or “I was in CYO,” (groups Friendship House had organized for children and teens).

On a later visit, when I asked to go to that church again, Joe and Audrey told me that they had decided to throw their lot in with their own parish, to work to make it better. So I went with them to their own ordinary parish.

My other memory is of staying overnight at the Monroes on a Saturday and lying awake all night listening to the sirens. All night, I prayed for the people those police cars and ambulances were going to and for all of Harlem.

Yes, Harlem was and is a place of much suffering. But after the ‘60s when Black people were finally able to move into other areas and many did, Joe and Audrey chose not to. “We don’t want to leave our people,” they told me.

Audrey carried the suffering of her people; it seemed never to be far from her thoughts. And she had those sufferings herself. Though not extremely so and sometimes more than others, Joe and Audrey were poor.

Audrey’s health was never good, something she attributed to the fact that she was malnourished as a child.

As the years went by, she became more and more overweight. And among other things, she suffered from glaucoma, which caused her vision to get deteriorate until she was almost blind. She was housebound for many years and bed-ridden for a few at the end.

Moreover, as is probably true of most poor people, she had many difficult struggles with bureaucracies.

But the amazing thing is that, though she told me about some of her suffering and I saw some of it myself, I have no memory of seeing her without peace.

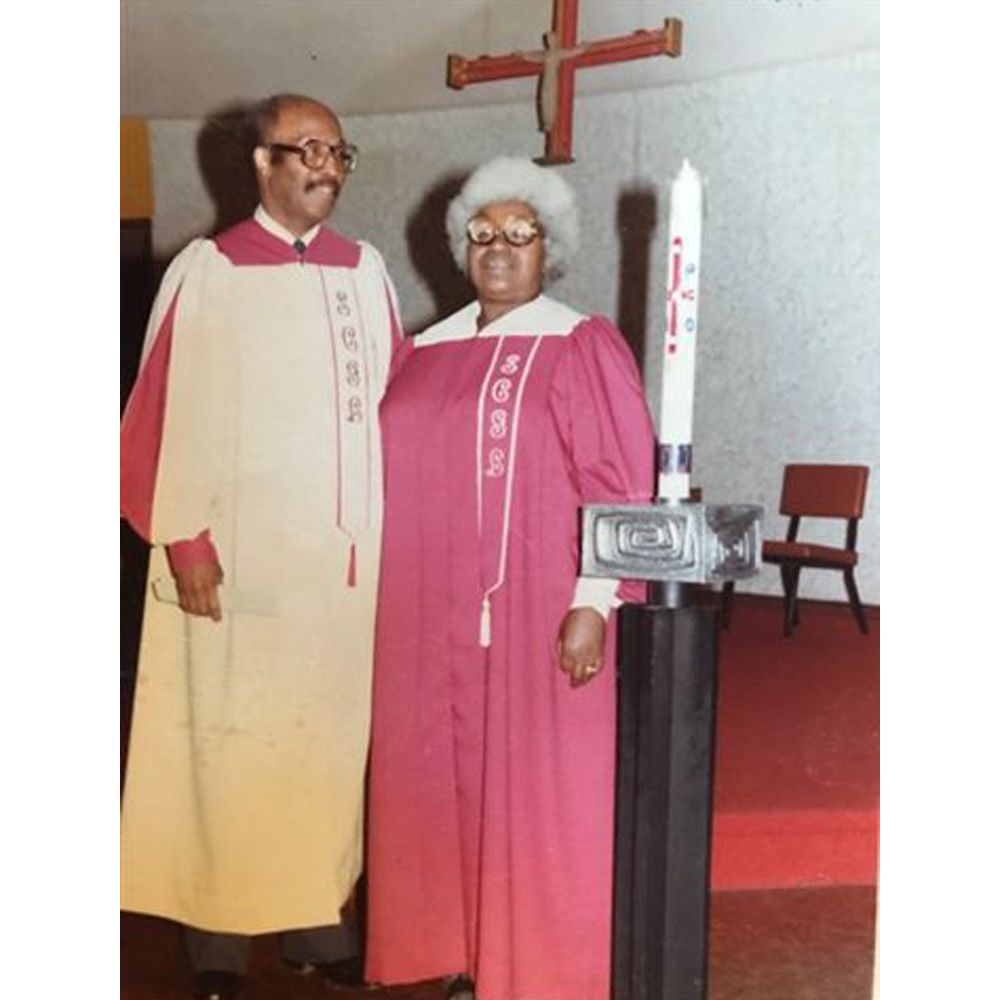

Audrey also had her joys. She loved music. She and Joe were in their church choir, St. Charles Gospel Lites, a group that once made a European tour. They also travelled to Africa in fulfillment of a dream. At the end of her life, Audrey asked for a cat, and she became her delight.

Most important of all, it was obvious that the source of Audrey’s life was God. She knew he loved her, and she talked to him as a friend. She asked him for what she needed, and she trusted him.

At some point, I came to realize that, though much of what Audrey was and lived came from her Black culture, much, too, she had learned and absorbed from Catherine Doherty and Friendship House.

This was especially evident in her ongoing hospitality of both house and heart. I think that that hospitality is what made people feel at home in her apartment as it makes people feel at home in all our Madonna Houses.

Audrey is much on my mind and in my heart these days, for she died recently—on November 20, 2017 at the age of 95.

What can I say but thank you, thank you, thank you—to Audrey and to God who brought her into my life. Of course, I will miss her, but how can I grieve when I picture her in heaven singing in ecstasy to the God she loves so much.

A form of consecrated life similar to religious life but composed of lay people living in the world.