This content has been archived. It may no longer be relevant

What does it take to be a pioneer? Those who joined Madonna House in the first decade after Pope Pius XII persuaded Catherine Doherty to propose some kind of promise of stability (1951-1961) were certainly pioneering a new apostolic venture in the Catholic Church.

While some might argue that Madonna House is still in the pioneering stages, it’s not quite the same now as it was back at the beginning, when people like Marité Langlois were choosing to join.

Here is one possible definition of the word pioneer: “a person or group that originates or helps open up a new line of thought or activity;” and also, “one of the first to settle in a territory.” That one is from a Webster’s dictionary.

A unique use of the word is found (in some translations) in the letter to the Hebrews, chapter 12: Let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who, for the sake of the joy that was set before him, endured the cross, disregarding its shame (12: 1-2).

Both sources are helpful in appreciating the contribution of the pioneering generation to movements in the Church.

So what pioneering qualities were found in Marité? Although she is descended from early settlers who came to Quebec from France in the 1630s, Marité didn’t exactly exemplify the rough-and-ready stereotype of bygone years.

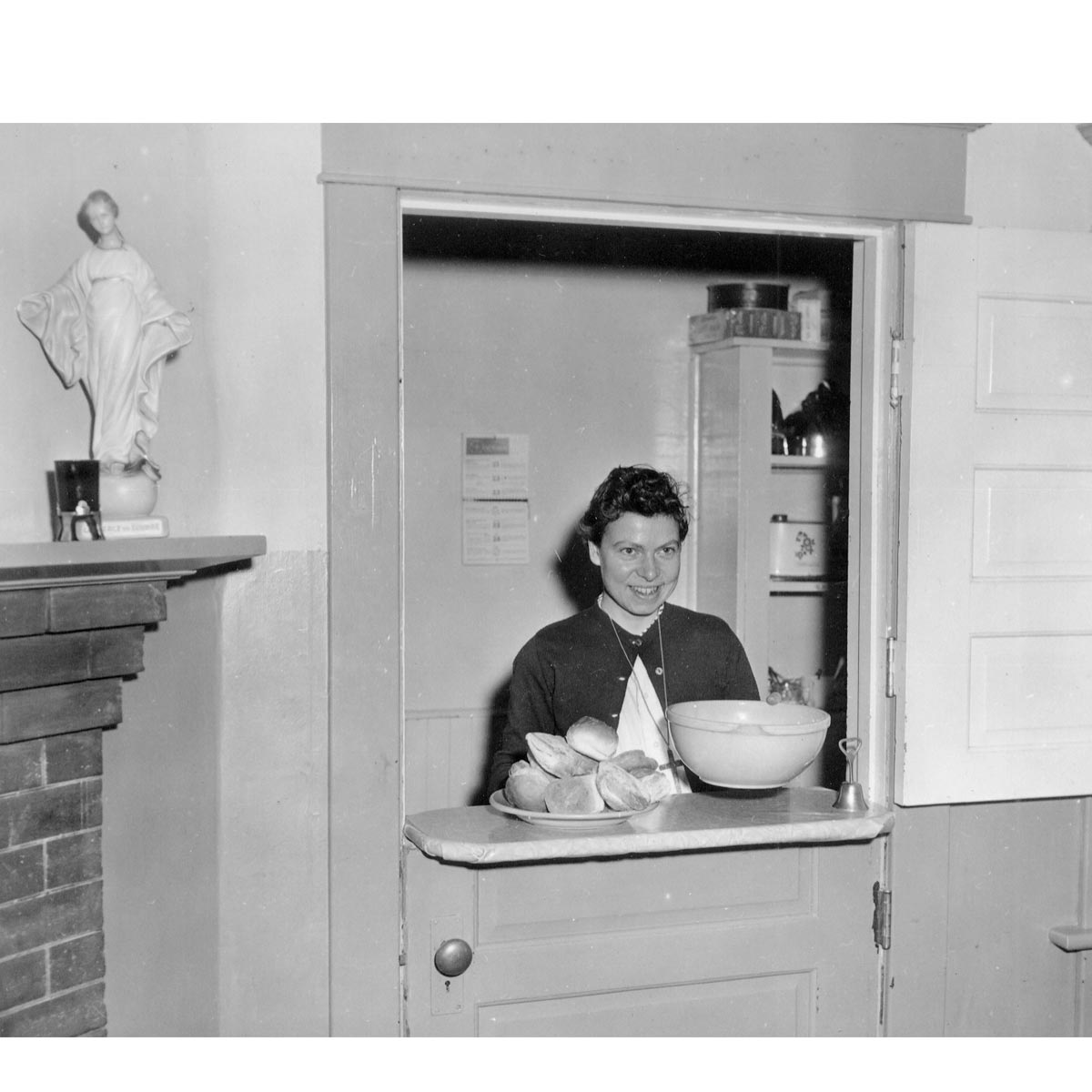

She was a pious Montreal girl with a certain air of refinement. She was somewhat particular in her preferences, had a sharp memory for details, and was trained as a stenographer. She was gregarious, loved playing (and winning at) cards, and was exemplary in the hospitality shown to guests.

Moreover, like so many of her generation, she struggled to believe that God is truly merciful, as opposed to being more an exacting Taskmaster whom one can never quite satisfy. None of these qualities, however, define the pioneer.

What does? First, Marité, like others who joined in her day, was taken by the inspiring presence of God that she sensed in Catherine Doherty.

It was strong enough to convince a whole generation to “take a chance” on Madonna House, which at that time had hardly any standing in the Church, and survived on the tenuous support of a few bishops here and there, the encouraging words of a pope, and the tremendous faith Catherine had in the mission God was giving her.

More than one of the first members to join has spoken to me about this gift of faith. It manifested itself as a burning desire to share the Gospel with the whole world, but also as a certainty that the love of God for us is real, alive, present here and now.

Who cared if Madonna House did not yet have the standing of the traditional orders, if the God Catherine preached wanted to start something new in the Church and was who she said he was!

However, it takes more than youthful enthusiasm, even enthusiasm fueled by a mature vision of faith, to persevere in a challenging vocation.

They worked hard in those early years. Long days merged into evenings given over to still further communal demands.

Catherine was inspiring; but she wasn’t necessarily easy to work with, or even understand at times.

The early staff must have agreed with Stanley Vishnewski of the Catholic Worker who said about himself and their “saint,” Dorothy Day, “It takes a martyr to live with a saint.”

Catherine inspired and pushed hard for greater generosity. And she herself exemplified in many ways an ideal which could be followed but not exactly imitated.

Many staff came and went, but pioneers like Marité had the gifts of perseverance, loyalty, and dedication to a unique degree.

There was a kind of toughness about Marité, despite her sensitivity and proneness to anxiety. This made me think of that famous line from St. Paul: God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong (1 Cor 1: 27).

Along with all this was a marvellous capacity not to take herself too seriously, despite or maybe because the purpose of the apostolate was so serious: to restore all things in Christ, especially the poorest of the poor and those furthest away from the Church.

Catherine often spoke with great passion about Christ suffering in his body, that is, in all kinds of people—and “What are we going to do about it?”

But there were often, as a kind of counterpoint, sing-alongs in the evenings, of 1950s (and older) songs, whose lyrics the staff re-wrote to describe Madonna House life, and which included gestures repeated over and over and over.

I can still see and hear Marité singing and acting out with enthusiasm one song having to do with introducing guests to some of our Madonna House “peculiarities.” The last words of each refrain—each with its gesture—were, “‘Nite, nite. Hi there!” And more. Yes, the urbane stenographer had come a long way indeed.

But there was another aspect to her spiritual life that was of vital importance: it was her devotion and love for her patron saint: Thérèse of Lisieux. One of the last books she was reading was yet another reflection on the life and spirituality of the Little Flower.

Thérèse’s Little Way, of course, helped to illuminate the spirituality of little things, and Nazareth that was being taught here by Catherine. And the starkness of Thérèse’s illness and death is similar to the teachings on the cross and on the suffering Christ that was being given here.

Suffice it to say that Marité derived great consolation from this saint to whom she felt so close.

Our early years here were well anchored in various aspects of the traditional spiritualities of the Catholic Church, notably the Carmelite and Franciscan, which blended well with the Russian dimension Catherine was bringing forth as time went on.

That Madonna House drew on so many currents of gospel truth in those early years is a tribute to the open-mindedness of that generation, beginning with the foundress.

Having our origins in rural Ontario in a little-known corner of Renfrew County did not prevent us from having foundations that were remarkably universal in scope.

That leaves me with two final points about our pioneers that seem universal, and one of which Marité especially exemplified: consecration to Our Lady and enthusiasm for the future.

As for the first: it is well known in our history how the consecration to Jesus through Mary is somehow foundational for our vocation. Mary is our vocation, and it is she who shapes us into her Son and the offering desired of each of us. Our Lady of Combermere is her visible manifestation, and Marité was one of her loyal children, for sure.

Perhaps because of this closeness to Mary, Marité had a great optimism about the future of Madonna House, and about the current crop of Madonna House members, especially those carrying responsibility and those just joining.

Her old cohort, Mamie Legris (a classmate from 1952), was of the same opinion. “What a great job the DG’s (directors general) are doing! We’re in capable hands.” “And the newest members, well, they’re simply terrific, much better than we were.” And so forth.

Eventually, you found yourself believing these ladies. After all, they are our pioneers, who helped to open a new “territory” for God’s work and kept their eyes on Jesus and Mary … and Catherine Doherty, forgoing immediate reward for the one God reserves for those who love him on this earth.